This review was written by contributing writer Thuy Dinh, an editor of the webzine Da Mau and my resident expert on graphic novels. —PCN

**************************************************************

As children, my cousin Allan and I would spy on Mrs. Seven, the mean lady who lived next door to our grandparents. She would pray to God then curse at children and beggars. We drew comic strips about Mrs. Seven, putting her in situations that literally exposed her hypocrisy, like having the wind blow away all her clothes on her way to church, leaving her naked, or her long wig snatched and eaten whole by another neighbor’s giant German shepherd.

As children, my cousin Allan and I would spy on Mrs. Seven, the mean lady who lived next door to our grandparents. She would pray to God then curse at children and beggars. We drew comic strips about Mrs. Seven, putting her in situations that literally exposed her hypocrisy, like having the wind blow away all her clothes on her way to church, leaving her naked, or her long wig snatched and eaten whole by another neighbor’s giant German shepherd.

Because I had so much fun drawing these strips with my cousin, I never thought they touched on anything serious. Later, when I grew older, I felt traditional comics—with their static panels of images and silent dialogue encapsulated in bubbles—were poor relatives of multi-sensory moving images in films.

And yet, I was completely blown away by Asterios Polyp, David Mazzucchelli’s latest “comic book,” a pull-out-all-the-stops package that’s funny, poignant and deep, with panels of thoughtfully shaded images that form a visual novel, a paper movie, and finally, an existential meditation on things that matter to us: religion, art, science, love and memory. In other words, Asterios Polyp manages to embody Up; Synecdoche, New York; and The Curious Case of Benjamin Button without losing its fluid eloquence or sly sense of humor.

At the beginning of the book, Asterios Polyp’s apartment is struck by lightning and, like ancient Troy, goes up in flame. His beloved wife, Hana Sonnenschein (whose Japanese-German name means Flower Sunshine), is nowhere to be found. The book, with flashbacks interspersed with the present, shows Asterios’s progress from hell and back. He is both Ulysses and Orpheus, someone who has to find his way home.

For a work presumably focused on images, Mazzucchelli has a lot of fun with words. Asterios is of Greek descent. His fancy name suggests a polarized nature: star and anal wart (“asterios” means “star, “polyp” can mean a rectal cyst). His dead identical twin, Ignazio, narrates the book and constantly reminds us that our hero is physically and metaphysically divided. Asterios, an arrogant and famous architect, creates buildings that are only models on paper because they have never been built (thus, he’s not unlike a comic book artist, whose world is rendered in two-dimensional images).

via Comic Book Resources

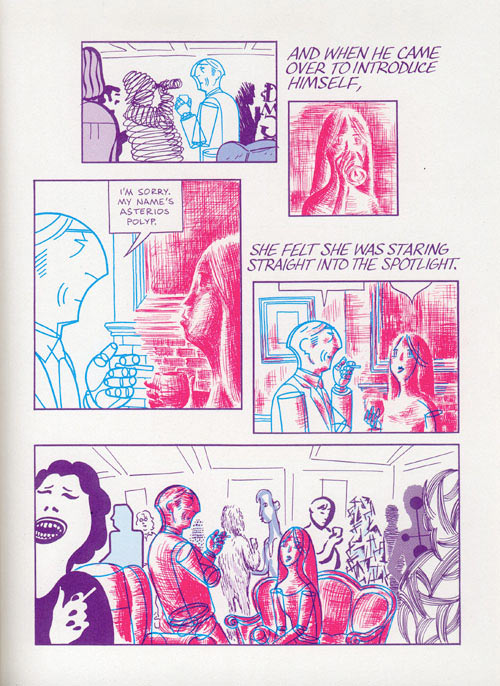

Mazzucchelli’s graphic novel is also a cosmic quest for beauty. The book is full of contrasting visual shapes, text fonts and color tones, with each form/palette tailored to the personality and philosophical outlook of each character. Asterios is often drawn in linear, geometric form, awash in cool blues. His wife Hana, on the other hand, is often depicted in softer, rounder lines and in warmer coral or pinkish tones.

Another character, Ursula Major (a pun on the constellation Ursa Major), who is like Ceres in Homer’s epic, is often rendered in bright yellow or deep purple squiggles as she represents a mystical earth mother type. This traditional cartoon technique of employing form and color to denote character was most recently seen in the movie Up, where the rounder, more exuberant form of the boy Russell is contrasted with the blocky, rigid lines that make up the old man Carl.

In essence, a story told by Asterios to Ursula Major serves as the main theme of the book: A wooden Shinto temple in Ise, Japan, originally erected in the 7th century, has since been ritually torn down every twenty years and rebuilt, and yet the Japanese would tell tourists the temple is 2000 years old. The riddle suggests that human existence, like a building that’s constantly being destroyed and recreated, must yield to larger forces in the universe.

Asterios, in his lofty reach toward the stars (toward perfection and permanence), doesn’t realize that stars, though lasting thousands of years, can also self-destruct. His search for the meaning of life, like his search for Hana, resonates via the myth of Orpheus—presumably, Asterios must go forward and never look back. The controversial ending of the book makes one wonder if Asterios has indeed gone forward.

Similarly, David Mazzucchelli’s ambitious effort, while shredding the comics/cosmic barriers, is a look back toward the traditional purpose of comics, the ability to wield simple lines and forms to capture—or destroy—everyday reality.

7 Comments

MelodyGirl

July 25, 2009 at 10:23 pmI don’t read a lot of graphic novels but I do love Greek mythology. You make a lot of interesting points.

I’ll see if my library has a copy.

Shelley P

July 26, 2009 at 1:39 amThanks for the in-depth and helpful review, Thuy Dinh. I’m not at all well versed with graphic novels, and you’ve given me a lot of food for thought and sparked my curiosity.

popculturenerd

July 26, 2009 at 9:58 amShelley P, since you’re an artist and writer, have you ever considered writing your own graphic novel?

Shelley P

July 26, 2009 at 7:58 pmGood question, PCN! I’ve only had the odd doodle with cartoon ideas. Now that I’m a bit intrigued with graphic novels, well, we’ll see …

Shelley P

July 26, 2009 at 1:40 amPS: I love the sound of your own Mrs Seven comic strips!

Debbie

July 26, 2009 at 10:54 amPCN,

Are you bringing in guest reviewers from the NY Times these days?? What a beautifully written and insightful review. I must confess I have never really looked at graphic novels through the prism of literary criticism–probably because I’ve never read them. Well, my eyes are now open, thanks to you, to a new kaleidoscope of colors, shapes, and fonts. Thanks for the stellar 3-dimensional review!

popculturenerd

July 26, 2009 at 11:43 pmThanks, Debbie, I’ll make sure Thuy sees your comments.

I’m not fluent in graphic novels but the Tintin, Asterix & Obelix, and Benoit Brisefer books were my first loves. They got me hooked on reading. I also think there’s greater profundity in the Calvin & Hobbes strips than in a lot of so-called literature.