This review is by contributing writer Thuy Dinh, a practicing attorney and editor-in-chief of the literary webzine Da Mau.

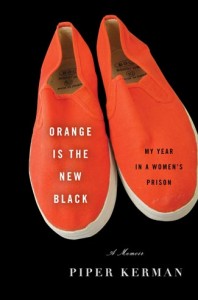

Piper Kerman’s memoir, Orange is the New Black, deftly invokes the themes of “white girl gone wrong” and No Exit. In fact, the memoir’s best selling point is the atypical profile of its author: a blond, blue-eyed Smith graduate who happens to be a federal offender, sentenced to 15 months in prison for a drug charge committed thoughtlessly in her “bohemian” youth. (Kerman was released after 13 months for good behavior.)

Piper Kerman’s memoir, Orange is the New Black, deftly invokes the themes of “white girl gone wrong” and No Exit. In fact, the memoir’s best selling point is the atypical profile of its author: a blond, blue-eyed Smith graduate who happens to be a federal offender, sentenced to 15 months in prison for a drug charge committed thoughtlessly in her “bohemian” youth. (Kerman was released after 13 months for good behavior.)

Early on in the book, Kerman describes her self-surrender at the women’s minimum security federal prison in Danbury, Connecticut with dissonant yet arresting (no puns intended) details: slowly shedding her identity before going behind bars by first taking off her seven gold engagement rings, then the multiple earrings from “all the extra holes that so vexed my grandfather.” In the lobby of the prison, she stalls the inevitable moment by munching on a foie gras sandwich chased with Diet Coke, wryly wondering if she is the only Seven Sisters graduate who samples her last gourmet meal at the entrance of a penitentiary. The book’s epigraph—lyrics from “Anthem,” a song by Leonard Cohen—says it all:

Ring the bells that still can sing

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack, a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in

The attraction of Kerman’s memoir is the story of a privileged, middle-class girl who transgresses, then later redeems herself through her own self-discipline and the emotional support of her family and prison peers. The horror of her condition is not unlike the horror of hell described by Jean-Paul Sartre in his famous play No Exit: hell is not an external condition like torture or physical pain, but the deprivation of one’s community and the relentless confrontation of the imperfect self.

Kerman’s prison, her version of hell, is in fact the classical notion that her self-worth and free choice as a functional member in society have been taken away due to her crime. Behind bars, a prisoner is forced to become institutionalized by accepting all the arbitrary rules, spoken and unspoken, about prison life. Yet, as Kerman reflects, the prisoner’s acceptance of her new environment reveals a cruel paradox: Most prisoners with long sentences are not given any preparation or emotional support to cope with the outside world once they are released. Like the characters in No Exit, prisoners are conditioned to feel as if they will never be free, even after all barriers to their physical freedom have been lifted.

Kerman is most effective in evoking this constant stigma: the strip search—the women are forced to remove their clothes, squat on the floor, and cough hard—after every visit or contact with the outside world, the grim notion that a prisoner’s words have no value if weighed against the “truth” as asserted by her jailer, the sight of small children being wrenched away from their mothers as the visiting hour ends, prisoners giving birth, then having to leave their newborns in someone else’s care before being whisked back to prison in shackles.

While Orange does not try to scale the cosmic questions raised in Crime and Punishment, its central message echoes the lesson learned by a penitent and existential Raskolnikov: Even if there is no God or no viable authority to guide anyone, a moral code exists naturally within the individual. This moral code makes him suffer once he transgresses. Yet the awareness of a moral code is like “a crack that lets in the light,” the very thing that redeems the individual in the end because it makes him realize he has the freedom to choose between good and evil.

When not in her introspective mode, Kerman speaks of the prison’s unspoken but entrenched code: No one is supposed to ask how anyone ended up there. The reader does not know specific details about many of the women’s crimes, only that most of them are amazingly kind, and fairly normal, like any woman who’s not in prison. They gossip, bicker, commiserate, give each other forbidden pedicures, cook prison food with the aid of a microwave (Kerman’s signature prison cheesecake serves as a nice contrast to her foie gras sandwich eaten prior to her admission).

But all this normalcy, meant to encourage public acceptance, is a bit disturbing. By making the world behind bars accessible to the average reader through her Margaret Mead observations, rendering Danbury as a gritty “all-girls high school” with West Side Story tribal overtones, where Kerman becomes healthier and thinner by running track and practicing yoga, the author occasionally dilutes or contradicts her message. While it’s unusual for a well-educated, girl-next-door type to land in prison, Kerman’s confinement does not make it more fashionable, more tragic, or more acceptable than for someone who comes from the wrong side of the social equation.

Orange should not, ever, be considered the New Black, given the personal stigma and erosion of self-worth that Kerman so eloquently evokes in the book’s more forceful, memorable chapters. I wish she had probed more deeply into other cases besides her own, to prove that the mandatory minimum sentences in non-violent drug cases are inherently unfair to defendants and financially disastrous to the country’s economy. (Kerman’s Justice Reform links on her website makes a better argument than her memoir). Nevertheless, Orange is the New Black should probably be required college-level reading on social justice.

Buy Orange Is the New Black from Amazon

Buy from Indie Bookstores

(I get a tiny commission from Amazon.)

6 Comments

le0pard13

May 9, 2010 at 9:06 amOne very fine book review, Thuy Dinh. Thank you for this.

EIREGO

May 9, 2010 at 1:14 pmWhile I hold nothing personal against author Piper Kerman and guest reviewer Thuy Dinh’s in depth review of Orange Is The New Black, I can’t help but feel a bit infuriated by this story. Will Bernie Madoff be writing a similar book when he finally gets out of prison? Or will he be able to publish while behind bars? I won’t be picking up any “literature” from the Enron/Wall Street jerks or those two female journalists who knowingly crossed into North Korea and got caught either.

The simple fact of the matter is Piper Kerman knew, as did the others mentioned in my little diatribe, they were doing wrong and got caught. They should not profit from any “enlightened” hindsight whatsoever.

I will not be adding to Kerman’s coffers by buying this book no matter how catchy the title.

Reader#9

May 9, 2010 at 1:22 pmSaw this at B&N the other day and was wondering if it was worth my time. Seven engagement rings? Foi gras instead of cheesecake? Oh, I gotta read this!

Shell Sherree

May 11, 2010 at 12:15 amThank you for such a considered and thorough review, Thuy Dinh! I’m not drawn to reading this book, but I really appreciate your thoughts and observations on it.

MelodyGirl

May 13, 2010 at 11:19 amHey, I wasn’t sure if I wanted to read this before but you’ve got me intrigued with the NO EXIT comparison. I also didn’t know people in prison aren’t allowed to ask each other how they got there. They do in movies all the time!

Thanks for a really intelligent write-up, Thuy.

Doreen Adams

July 5, 2014 at 7:18 pmI enjoy the Netflix series. Reading the book, Don’t think I’d like the real Piper. Foie Gras. Really ? I hope you gained empathy of vulnerable populations during your prison stay.