This review is by contributor Thuy Dinh, coeditor of the literary online magazine Da Mau.

In Leni Zumas’s lyrical yet unsparing novel, red clocks symbolize the identity crises, haunting wombs, ticking time bombs of five female characters: the Biographer (Ro Stephens); the Polar Explorer (Eivor Minervudottir), a nineteenth-century scientist and elusive subject of Ro’s unpublished book; the Mender (Gin Percival); the Wife (Susan Korsmo); and the Daughter (Mattie Quarles).

In Leni Zumas’s lyrical yet unsparing novel, red clocks symbolize the identity crises, haunting wombs, ticking time bombs of five female characters: the Biographer (Ro Stephens); the Polar Explorer (Eivor Minervudottir), a nineteenth-century scientist and elusive subject of Ro’s unpublished book; the Mender (Gin Percival); the Wife (Susan Korsmo); and the Daughter (Mattie Quarles).

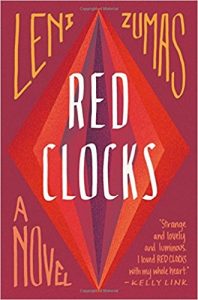

The bold crimson design on the book cover resembles an abstract, open-yet-closed vagina, which beautifully complements the epigraph by Virginia Woolf on the inside page: “For nothing was simply one thing. The other Lighthouse was true too.” Both the design and the epigraph reflect the ambivalence of inhabiting one’s womanhood.

In Red Clocks, four of the five women see themselves as disenfranchised from their ideal selves.

Ro, despite having a meaningful intellectual life as writer and high school history teacher, repeatedly fails to conceive by artificial insemination.

Eivor can’t author a book under her own name on the patterns of polar ice during the Victorian era, and is forced to use a male colleague’s name.

Susan, a law school dropout, resents the tedium of child-rearing and housekeeping while insisting a woman’s maturity comes from the fulfillment of her reproductive destiny.

And Mattie, a high school sophomore, aspires to a career as a marine biologist but gets impregnated by a vain and dim-witted boyfriend.

Gin, a homeopathic healer, is the only character who feels fully at home in her body and natural habitat. She, however, is ostracized as a witch by the townspeople.

While certain readers may be quick to label Red Clocks a dystopian novel, its depiction of a present-day United States where the Twenty-eighth Amendment bans abortion—and grants rights to life, liberty, and property to every embryo—functions more or less as a McGuffin. The harmful consequences resulting from this regime occur mostly offstage, and serve to heighten the characters’ conflicts but don’t represent the novel’s center.

Even without the Supreme Court’s reversal of Roe v. Wade and the abolition of Planned Parenthood, as the novel imagines, the characters’ struggles would still exist, because the idea of being a woman with choice is still open for debate in the twenty-first century.

Even without the fictitious Twenty-eighth Amendment, an unwanted or out-of-wedlock pregnancy still raises questions of decorum and ethics in certain milieu. Its inverse scenario—of a single woman wanting a child via artificial or in vitro fertilization—still entails considerable financial and emotional costs.

Zumas shows that her characters do not behave as a result of some legal construct, but in spite of it. Gin, who became pregnant as a teenager, did not terminate her pregnancy during the era when abortion was still legal, but chose to carry her baby to terms before giving it up for adoption.

Mattie, on the other hand, chooses to end her pregnancy despite the serious health and legal risks posed by the antiabortion regime. And Penny, Ro’s colleague at the high school, writes passionate novels in which Irish nurses have urgent and unprotected sex with hot, “britches-bursting” Italian stallions.

With humor and compassion, Zumas also describes how silence, judgment, and cowardice imprison her characters.

Susan, saddled with unruly children and envious of Ro’s freedom, nonetheless gloats that Ro is single and unable to have a baby. Ro, while mocking Susan’s choice of taking her husband’s last name, yearns for Susan’s lifestyle as a financially stable, married, stay-at-home mom.

Mattie’s adoptive parents are loving and protective, yet quick to judge unconventional life choices and cannot accept a scenario where Mattie might not be born. Even Gin, though kindhearted, will not save her lesbian lover from domestic abuse if that means she has to give up her own independence.

In lieu of pat resolutions, Red Clocks offer intimate, redemptive moments when the characters fully embrace their estrangement. It provides an excellent roadmap to the country of female awareness.

The above is an affiliate link that, if used, could provide PCN a small commission.